Some notes on the aesthetic of progress

Progress art as harmony between technology and nature

George Inness's 1855 painting “The Lackawanna Valley” (shown below) captures a transition point in the history of the United States. The rapid growth of the railroad system in the 1800s carved up vast tracts of land, connected the country, and extended expansionary fingers westward. The distance covered by railroad lines grew from almost nothing in 1830, to 5,000km by 1840, 14,000km by 1850, and then 50,000km by 1860. Growth accelerated after the 1860s; the network reached its greatest extent in the early 1900s, with 400,000km of tracks laid. Some modern readers might expect this lively progress to have stirred up feelings of fear or unease among those witnessing it first-hand1. But this is not the impression given by “The Lackawanna Valley” — rather, we’re presented with a harmonious and even romantic scene of technology cohabiting with nature.

“The Lackawanna Valley” is an exemplar of a trope in American art, one that the historian Leo Marx refers to as the “Machine in the Garden” in his 1964 book of the same name2. The rapid industrialisation of America in the 19th century bled through to the era’s paintings and literature, where ‘machines’ (mostly trains) begin to appear with some regularity in depictions of the ‘garden’ of the American countryside. Technological progress manifested by the encroachment of these machines was then seen in a broadly positive light. To the citizens of the newly independent United States, the land was a new Eden, or paradise, that they were destined to conquer — with the aid of technology.

One of the more spirited affirmations of the American perspective on progress at the time is given in Timothy Walker’s “Defence of Mechanical Philosophy,” which reads like an 1831 version of the Techno-Optimist Manifesto. In it, he says:

“Where [Nature] denied us rivers, Mechanism has supplied them. Where she left our planet uncomfortably rough, Mechanism has applied the roller. Where her mountains have been found in the way, Mechanism has boldly levelled or cut through them. Even the ocean, by which she thought to have parted her quarrelsome children, Mechanism has encouraged them to step across. As if her earth were not good enough for wheels, Mechanism travels it upon iron pathways. Her ores, which she locked up in her secret vaults, Mechanism has dared to rifle and distribute. Still further encroachments are threatened. The terms uphill and downhill are to become obsolete. The horse is to be unharnessed, because he is too slow; and the ox is to be unyoked, because he is too weak. Machines are to perform all the drudgery of man, while he is to look on in self-complacent ease.

But where is the harm and danger of this?”

Walker wrote his defense as a response to the pessimistic view of technology espoused by the Scottish essayist Thomas Carlyle. Carlyle feared that the spread of technology would lead to the loss of an essential human character; a spirtual connection to the land and nature replaced with an mechanical, unnatural connection to artifice. Walker responds that freedom from biological shackles and toil allows us time to attend to our minds: the less labour we need to perform, the more “time left free for nobler things.”

“In the absolute perfection of machinery, were that attainable, we might realize the absolute perfection of mind. In other words, if machines could be so improved and multiplied, that all our corporeal necessities could be entirely gratified, without the intervention of human labor, there would be nothing to hinder all mankind from becoming philosophers, poets, and votaries of art. The whole time and thought of the whole human race could be given to inward culture, to spiritual advancement.”

Here Walker speaks of technology in quasi-religious tones; he sees technology as a means of ascension towards a higher state of being. In philosophy, there is the concept of the ‘sublime’ — the reverence, or awe, we feel in the presence of immense power or greatness — that is often linked to such religious feelings. In “The Machine in the Garden”, Marx claims that from the rapid pace of progress in the 19th century emerged the sense of the “technological sublime”: the transfer of these feelings of awe from religion or the natural landscape to technology. Trains, factories, and industry is the sublime power of humanity manifest in mechanism.

It is this feeling of the technological sublime, and mastery over nature, that is common to much of the art that embodies the ‘progress aesthetic’ — an optimistic view of technology as an improving force for humanity. I propose that art in this class has the following attributes:

Technology as sublime

Technology as romantic

A juxtaposition of nature and technology; a harmonious cohabitation

Orderly nature; nature brought into service of humanity. Mastery and control over the natural world

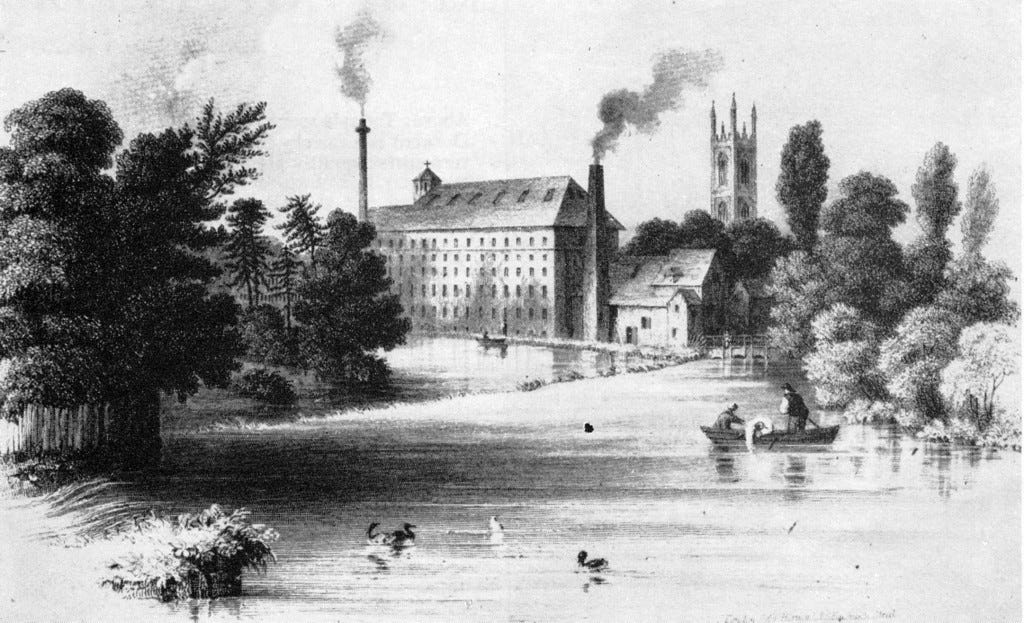

Below are several additional examples of this aesthetic. First, an engraving of Lombe’s mill (1750), the first water-powered silk throwing mill in England.

“Manchester from Kersal Moor” by William Wyld (1852). A watercolour commissioned by Queen Victoria of Manchester, then the largest producer of cotton textiles in the world.

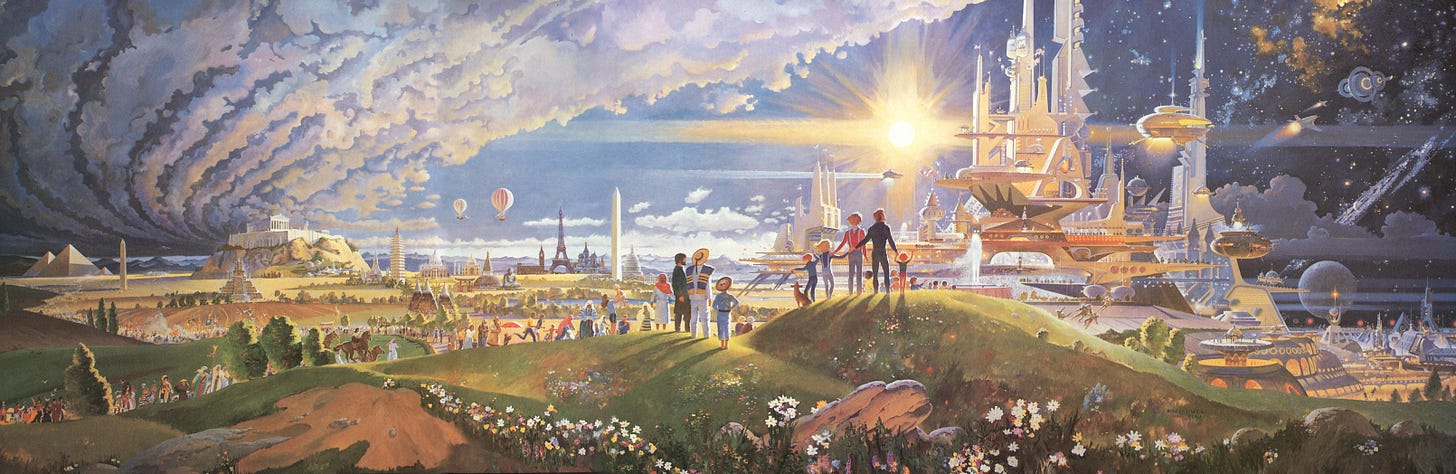

Robert McCall’s “The Prologue and the Promise” (1983) commissioned by Disney’s EPCOT centre as part of the Horizon’s exhibit that aimed to inspire parkgoers with an optimistic vision of the future (now closed).

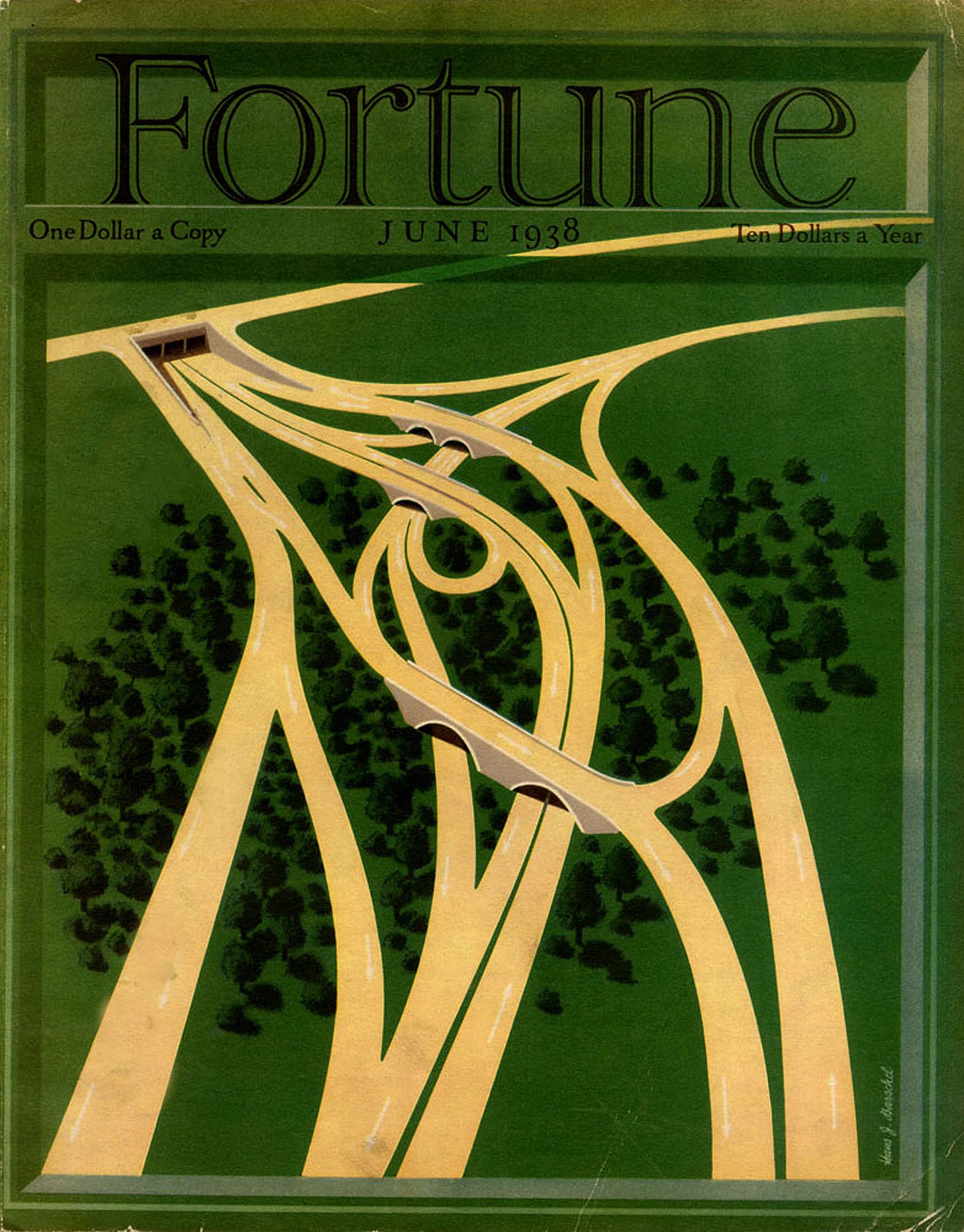

A Fortune Magazine cover from 1938.

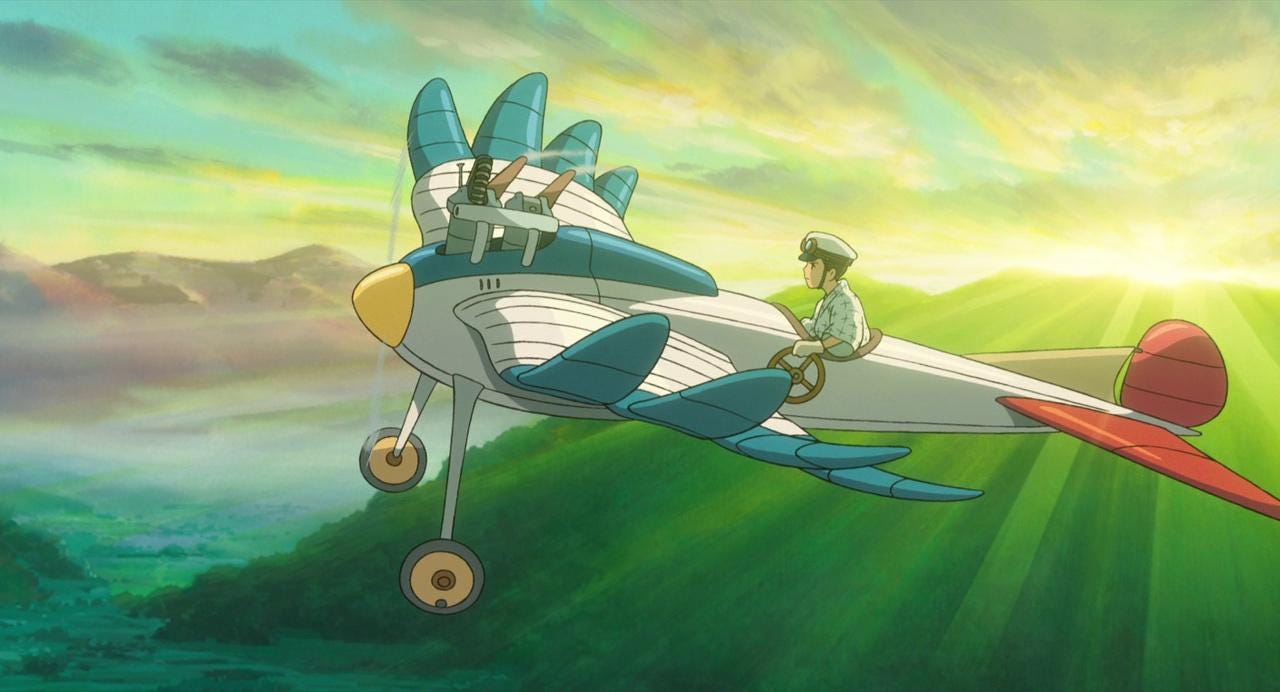

Miyazaki's works also often have this character of ‘progress art.’ Yet, his films are not purely optimistic; they often deal with the tension between the ideal of technology as an enabling force, and its destructive power. Miyazaki is most romantic when it comes to flying machines: this shot is from the 2013 film “The Wind Rises.”

Progress entails tradeoffs and preferences, and meaningful progress is inherently humanistic. Carlyle was right in arguing that a future wholly separate from nature is undesireable; we are biological after all, and a human-centric concept of progress acknowledges that. Marx, in his book, is also interested in exploring the balancing act between the pastoral ideal and maximum technological progress; the “Machine in the Garden” trope sees control over nature as desirable, but not its elimination.

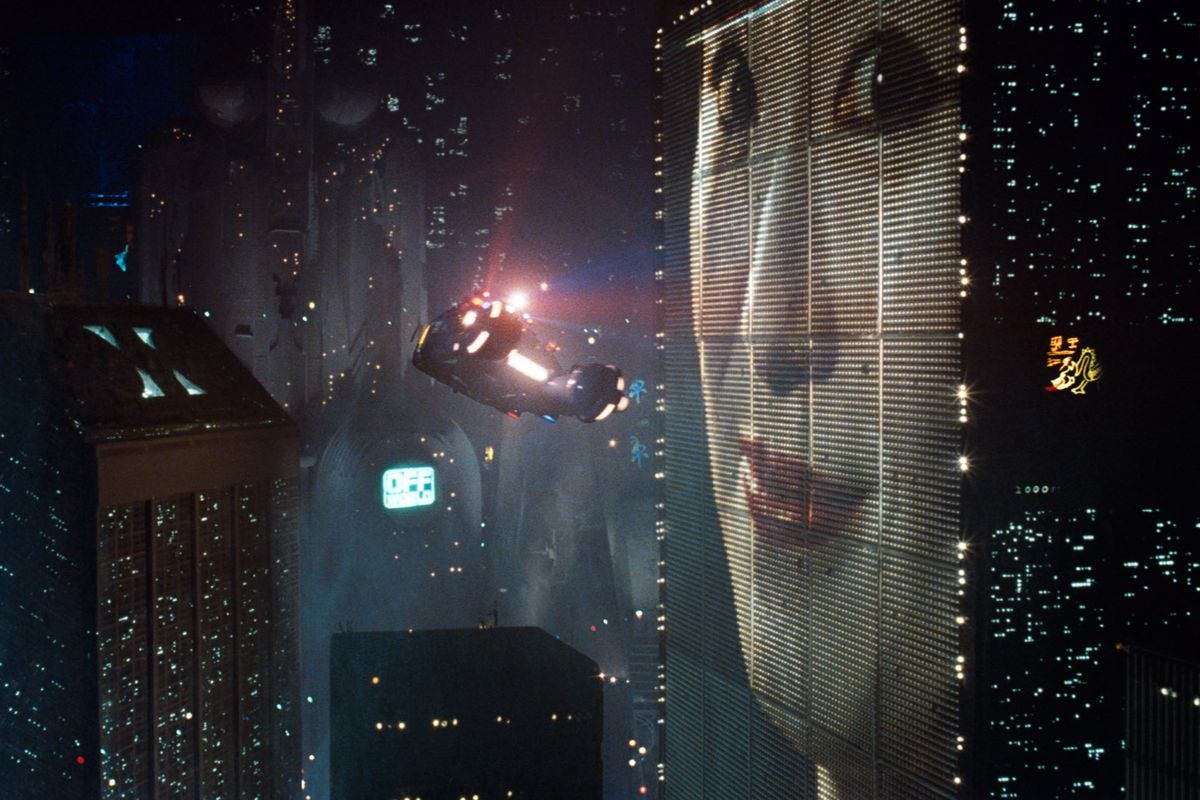

Along these lines, we generally find art in which technology has fully subsumed nature to be dystopian: for example, in the cities of Blade Runner (1982)

or Akira (1988).

But even in the absence of total assimilation, contemporary art often shows technology and the artefacts of civilization as being discordant with nature. Take Banksy, arguably the most publicly influential artist of the 2000s. In Banksy's world, technology, capitalism, and modern society are oppressive forces:

"We don't live in a world like Constable's Haywain anymore and, if you do, there is probably a travellers' camp on the other side of the hill. The real damage done to our environment is not done by graffiti writers and drunken teenagers, but by big business... exactly the people who put gold-framed pictures of landscapes on their walls and try to tell the rest of us how to behave."

This attitude is perhaps best displayed in his work “Show Me The Monet” (2005), where discarded shopping carts and a traffic cone litter Monet’s water-lilly pond.

Optimism about technological progress seems to be lacking in contemporary art. Perhaps it’s because most of our technological progress in the past generation has come in the form of information and computation — the internet, mobile phones, or AI — which doesn’t translate to visual mediums quite as well as trains or planes do. Yet, we still have modern technological marvels capable of evoking feelings of optimism and the sublime: rocket launches are arguably the modern equivalent of cathedrals.

So perhaps the problem is cultural; we’re lacking new, positive, visions of the future that put humans at the centre without disconnecting us from our natural origins. Perhaps it’s time for a 21st century version of “The Lackawanna Valley.”

The painting was commissioned by John Jay Phelps, the president of the Lackawanna Railroad company, as a form of advertisement for rail routes. Inness was a painter of bucolic, natural scenes — initially, he didn’t see the aesthetic appeal of rail technology, but he needed the money and eventually came around. Perhaps the stumps are minor form of protest, showing that the transformation of the landscape (and associated displacement of the native population) was not entirely without cost

Thanks to Professor Bedell for introducing me to Leo Marx

Notable in the early debate about mechanization is the naive lack of concern about pollutants. When the machine occurs as 5% of the landscape it appears pretty benign,because there is an obvious opportunity to get away from it. When the machine overtakes and overwhelms the natural world, it becomes oppressive in its dominance, making the fragility of the natural world obvious and frightening.

This is such a beautiful piece! My husband works in refineries and he’s always said he wants to make a coffee table book of all of the factories in these picturesque settings. We’ve visited a lot of them and they are always settled in the mountains, along streams and glaciers. They remind me of that portrait, and your aesthetic of industry in harmony with the natural world. I loved this.