But does surgery really work well without the FDA?

Or maybe the FDA is good actually

Recently, Maxwell Tabarrok has been putting out pieces on Substack arguing that the FDA should be abolished. As evidence for his position, Maxwell argues that surgery has managed to innovate effectively without FDA oversight:

I disagree:

I think the FDA is an important — albeit flawed — institution that should be reformed in a careful and incremental manner

I don’t think surgery is a good analogue for pharmaceuticals ex-FDA

Since Maxwell quoted me in the opening of his surgery post, I feel somewhat obligated to respond directly and justify my position. While I have some sympathy with the libertarian worldview, I’m here to argue that we’re not yet ready to tear down Chesterton’s fence.

For those who don’t want to read the full linked post, the structure of Maxwell’s argument, as I understand it, is as follows:

Both drugs and surgical procedures are complex medical interventions; it is just as hard for patients and regulators to assess the value of surgical procedures as it is for them to assess the value of pharmaceutical drugs

Unlike pharmaceuticals, surgery is not regulated by a central (federal government) agency like the US FDA

Despite a lack of centralised oversight, surgery functions well; surgery is constantly improving, and is not overrun by scams and ineffective procedures. At the very least, our surgical procedures do not outwardly appear to be of meaningfully lower quality than our drugs

Therefore, centralised government drug regulators like the FDA are not required to protect consumers from potential harms associated with complex medical interventions

Therefore, we should get rid of the FDA. This would increase pharmaceutical innovation by removing barriers to market without meaningfully increasing the risk to consumers

Before I address the comparison to surgery, and whether or not it’s valid, I want to note that there’s really no need to grasp for analogies like car manufacturing or surgery in the first place. We already know what an unregulated or loosely regulated pharmaceutical market looks like — and, reader, it’s bad.

Maxwell argues that in the absence of government oversight, market forces would prevent companies from pushing ineffective or harmful drugs simply to make a profit. Except that there are precedents for exactly this scenario occurring. Until they were stamped out by regulators in the early 20th century, patent medicine hucksters sold ineffective, and sometimes literally poisonous, nostrums to desperate patients. We still use “snake oil” today as shorthand from a scam product.

If patent medicines are too dated an example, we can instead look to the loosely regulated supplement industry as a proxy. Supplements often don’t contain what they claim to contain1, are frequently found to be ineffective in large randomised controlled trials, or are downright harmful to health. For otherwise healthy people without deficiencies, it seems likely that supplementation is mostly a waste of money2. Homeopathy is another example of a class of products with scant evidence to support their use; clearly people remain susceptible to bogus medical claims when they are willing to pay for treatments that are chemically indistinguishable from water.

The FDA did not spring into existence fully formed, its powers were granted and expanded over time in response to specific safety scandals and societal pressure (I cover these events in some detail in act 3 of my long post on the history of the pharmaceutical industry, thalidomide being the most notable). Anyone proposing we eliminate the FDA should keep in mind that we’ve already tried an unregulated pharmaceutical industry, and we decided that we didn’t much like it, thank you very much.

We can even point to recent examples of drugmakers pushing harmful drugs despite purported regulatory oversight. As Nick Laing notes in a comment on Maxwell’s piece, the opioid crisis is concrete, modern, example of how an overly permissive regulatory apparatus can lead to tragic outcomes:

“I won't get into the weeds of why treating medicine as a regular commodity in the market can lead to disaster, but the obvious example is the opioid crisis in the U.S.A. The market-friendly policies allowed heavy marketing of opioid medication both to patients and doctors (most countries in the world don't allow this) which, along with poor regulation of doctor prescription practises (and a bunch of other reasons) contributed to the U.S.A being one of the first high income countries in the world to have a reduction in life expectancy.”

The generic drug quality scandals documented in Katherine Eban’s book “Bottle of Lies” provide yet another example of how lax regulatory enforcement can incentivise drug companies to cut corners. Quoting a review of Eban’s book in NPR:

“In the U.S., FDA inspectors can show up to a plant at any time, incentivizing companies to always be in compliance lest they be caught off guard by an inspection. But the globalization of the pharmaceutical industry complicated this practice. To minimize diplomatic tensions, the FDA notified plants months in advance of visits. Such lead time gave overseas companies ample time to prepare for inspections. Eban describes accounts of companies hurriedly cleaning workspaces, shredding records and fabricating documents, even destroying visibly contaminated drugs.”

Anyone who wants to convincingly argue for disbanding the FDA should be able to show how we will avoid a repeat of these historical issues.

Now onto Maxwell’s actual argument re. surgery, against which I will advance three main counterpoints:

Surgery is regulated to a high degree. It is simply regulated differently to drugs (in a manner which indirectly involves the FDA, anyway)

It is generally more difficult to evaluate the risk-benefit tradeoff for drugs versus surgical procedures

In many cases, surgery doesn’t actually work all that well

Surgery is regulated

In the US, surgery is heavily regulated, albeit at a more local level than pharmaceuticals. The training process to become a practicing surgeon takes upwards of a decade (4 year undergrad, 4 year medical degree, 5 year surgical residency). State licensing boards can restrict surgeons from performing certain procedures, and take away their ability to practice if they do harm. Malpractice suits, guidelines (whether at the level of the hospital or professional associations), and peer training are other mechanisms that constrain a surgeon’s ability to act with impunity.

At the state and federal level, regulation is applied to procedures or surgical facilities (e.g. Joint Commission accreditation). Experimental surgeries generally require review and approval of a institutional review board (IRB) before they can be attempted. Much like in drug development, surgeons will test new procedures on surgical animal models before progressing to human experiments — the innovation process is controlled less by central diktat, but instead by the judgement of peers and ethics committees.

Now, one could argue that if the surgical profession can partially self-regulate, why not drugs? It’s plausible we could benefit from a variety of regulatory models adopted across institutions and states. For one, there is the practicality of interstate commerce; drugs can pass state borders more easily than surgeons. The other problem is one of scale. A great benefit of drugs is that they can be manufactured and distributed en-masse. But scale comes with risks, and as we saw with OxyContin, a harmful drug can do great damage when distributed widely. A single renegade “pill mill” can serve huge numbers of customers, whereas a rogue surgeon is limited in how much damage they can do.

And yet, the FDA is involved in regulating surgery (albeit indirectly). The FDA regulates the drugs used in surgery, like local anesthetics, anticoagulants, and antibiotics. The FDA also regulates devices from pacemakers to artificial heart valves to surgical robots (as Maxwell points out). Even stitches and scalpels fall under the jurisdiction of the FDA. Much of the progress in surgical outcomes has come from improved procedures enabled by innovative new FDA regulated devices, like the artificial heart valves used in transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR).

For patients ineligible for open heart surgery, FDA-regulated devices used in the TAVR procedure (in the case, the Edwards Sapien heart-valve system) cut deaths in half versus the previous standard of care (medical management with or without balloon aortic valvuloplasty).

The modern surgeon has many tools at her disposal, most of which have been touched by the FDA on their path from invention to the operating theatre. I happen to think this point is by itself sufficient to invalidate most of Maxwell’s argument. Surgery is not this counterfactual regulation-free analog to pharmaceuticals; surgery is also heavily regulated and anyway so confounded by FDA involvement I don’t think we can conclude much of anything from the comparison. But let’s continue regardless.

Pharmaceuticals are (typically) harder to evaluate than surgery

I don’t intend to minimise the practical difficulty of surgery, but there is often a simple mechanical causal logic to why surgeries work. Reductively, surgical procedures:

Remove a bad thing (e.g. a cancer)

Replace or repair a damaged or broken thing

Disconnect things that shouldn’t be connected

Close a hole that shouldn’t be there

Or as the 16th century French surgeon Ambroise Paré put it:

"To eliminate that which is superfluous, restore that which has been dislocated, separate that which has been united, join that which has been divided and repair the defects of nature."

Drugs, by contrast, tend to have subtle effects; it can take years of clinical trials before the effects of a new drug can be statistically separated from noise. I’m optimistic our ability to make these inferences will improve eventually, but we just aren’t good enough yet at predicting when drugs will work to comfortably skip clinical trials. We often don't even know how our drugs work at all. As I said in a comment on one of Maxwell’s articles:

“Most drugs that go into clinical trials (~90%) are less effective or safe than existing options. If you release everything onto the market you'll get many times more drugs that are net toxic (biologically or financially) than the good drugs you'd get faster. You will almost surely do net harm, especially when you consider that companies will be less rigorous about selecting compounds for development than today.”

The low-level substrate that drugs act on in our body is so byzantine that we cannot (yet) disentangle the long and interwoven causal chains that drugs put into motion. Because surgery acts at a higher (macroscopic) hierarchy, much of this underlying complexity can be abstracted away; surgery is to classical mechanics as pharmacology is to quantum mechanics.

Consequently, the effects of surgical interventions tend to be more predictable, and often much more dramatic, than drugs. This relative simplicity is part of the reason why we’ve had effective surgical procedures for hundreds (even thousands) of years and effective drugs for only a century or so.

Even so, drugs as obviously beneficial as Kalydeco (ivacaftor), Spinraza (nusinersen), and Gleevec (imatinib) do come along from time to time — and when they do they are brought to market quickly. It only took two and a half years from Gleevec’s first clinical trial to its FDA approval for chronic myeloid leukemia (the FDA review took 10 weeks).

Surgery often doesn’t work all that well

In his post, Maxwell uses data on surgical inpatient and operative mortality to support his claim that surgery is improving over time. Even though I think data on iatrogenic harm is weak support for Maxwell’s claim (a lead-free sugar pill is hardly meaningful progress), it’s plainly obvious that we’re better at surgery now than in the 1950s. After all, back then we were still lobotomising people.

But have we really improved more at surgery than we have in pharmaceuticals? That’s unclear, and the strong form of Maxwell’s argument would have established that claim using comparative outcomes data between the two classes of interventions.

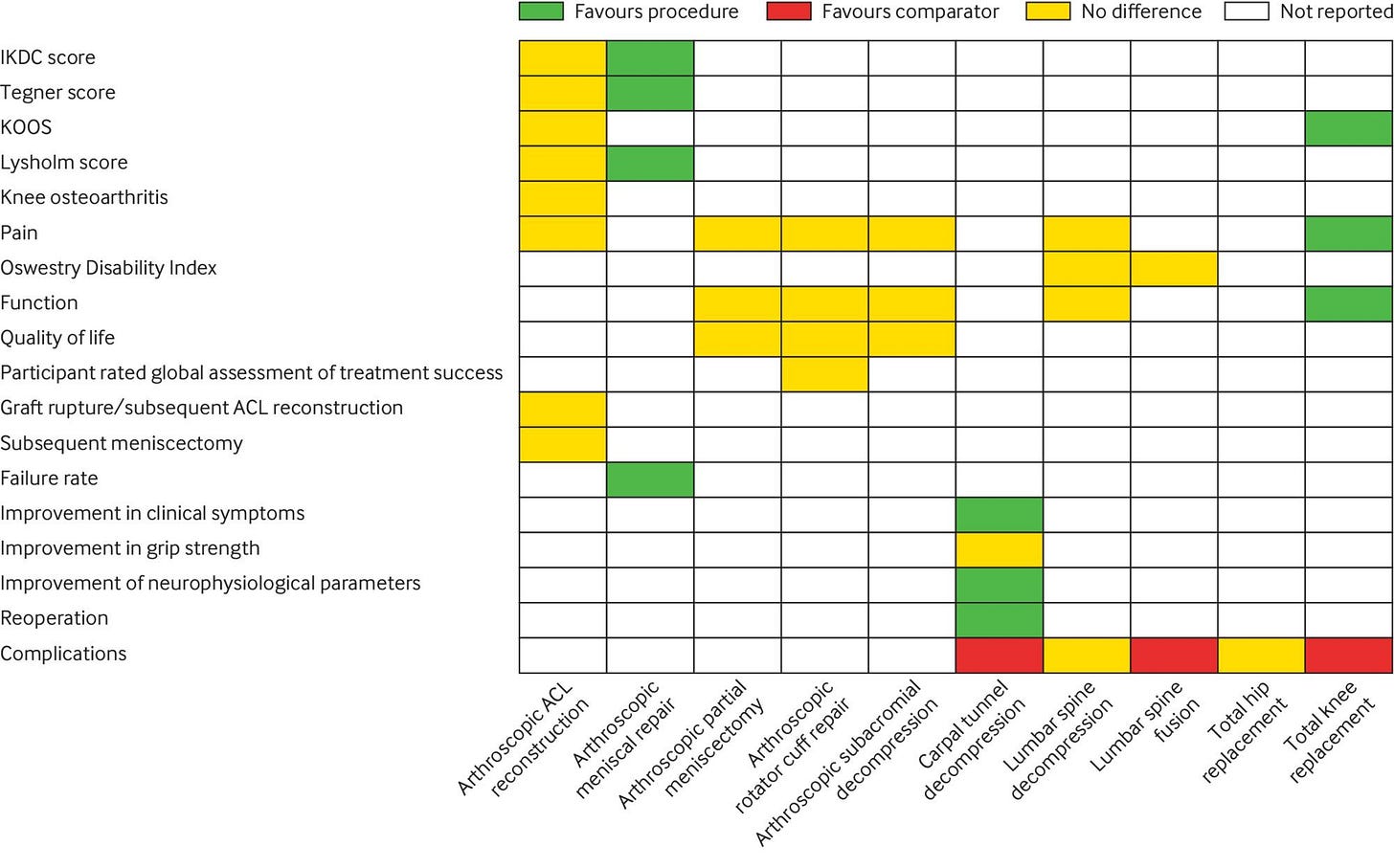

As far as I know, the dataset to conclusively establish the rate of improvement in the aggregate risk-benefit of surgery as compared to drugs doesn’t exist. We can, however, look to randomised clinical trials on surgical procedures to get a sense of the value of common surgical procedures. The benefits of excision of early-stage cancer, liver transplants, and trauma surgery are fairly unequivocal, but many other procedures fail to outperform placebos in randomised controlled trials. Orthopedic surgery in particular has a shaky evidence base: a review in the BMJ concluded that 7 out of 10 common procedures performed no better than non-operative management. And these are among the most common surgical procedures!

Consider also devices like the surgically implanted transvaginal mesh used to treat pelvic organ prolapse until they were banned by the FDA. These meshes were widely implanted, but frequently led to “mesh erosion, pain and pelvic infection” that necessitated another procedure to have them removed. Had the FDA not been involved in reviewing the evidence and issuing the ban, these harmful devices would probably still be used today.

In the end, all I can really say is that I remain unconvinced of the case for the wholesale destruction of the FDA.

Is the FDA perfect? No. Could it be better? As I’ve written before, I think the barriers to market could be lowered for diseases where clinical trials are infeasible or the unmet need is high. I also could be convinced of the value of parallel paths to market, like Scott Alexander suggests in his FDA post. It’s plausibly good to have diversity in review approaches that increase consumer choice. But, since the real gatekeepers to market access are often payers (and not the FDA) I’m skeptical these pathways would make much of a practical difference anyway.

To close out, I think it’s worth briefly considering the steelman argument for how drug regulators may help rather than hinder progress and innovation in pharmaceuticals. While it’s hard to establish causality here, I find the following arguments plausible:

The existence of the FDA is forcing function which incentivises drug companies to generate data that shows that their drugs have a positive risk-benefit profile. Information on what works and doesn’t work is fed back into the development process for future drugs, improving the quality of future drug development decisions

(as a corollary to #1) Because drug companies make money if their products are demonstrated to work, they are incentivised to pursue scientific research in a truth-seeking manner. Over time, market forces conspire to eliminate companies that do bad science and reward those who make discoveries that benefit humanity. By creating a mechanism for the market to reward good science, academic science (as a source of talent and ideas for biotech) is also indirectly incentivised to produce higher quality work

By creating a regulatory pathway which encodes some value judgements on what type of technologies are worth developing and in what manner, regulators can help funnel talent, money, research, and economic activity (incl. entrepreneurship) down channels that are ultimately beneficial for society

A defined regulatory pathway with established value generating milestones (IND, phase I, phase II, phase III…) makes investing in biotech more predictable and attractive3

I’m curious to hear counterarguments to these four speculative claims, or anything else I said in this post. Maxwell, back to you.

As a partial counterpoint, Scott Alexander looked into this claim and concluded that the quality of supplements is mostly fine. In his words: “Most simple supplements, including vitamins, minerals, and amino acids, are very likely to have the amount of product shown on the label. A few less reputable brands might differ by 25%, rarely 50%, practically never more than that.”

I would like to see a real attempt at a post evaluating whether the supplement market has improved over time.

In soft support of this argument is historical data showing that the number of active companies who introduced at least one medicine to the US market continued to grow after the tightening of FDA regulations in 1962

I think you make some good points but you kinda overplay your hand in a number of places -- and while I ultimately tend to agree with you it's for the opposite reason.

1) Good point about surgeons being regulated by licenscing boards etc...but the fact that surgeons use anaesthetics or implant devices approved by the FDA is kinda besides the point (lots of variation in surgical technique besides the drugs and devices). So kinda weird to make it the title.

2) Is it really true that the effects of drugs are harder to measure of do we just hold them to a higher standard?

I mean, given that surgery is regulated as you describe if it is so much easier to determine its efficacy then how can it be that often it doesn't work that well?

More specifically, most drugs actually also so something pretty clear cut (put you to sleep, reduce cholesterol, kill bacteria, inhibit virus replication, reduce pain etc). They all do something clear cut if you include descriptions like: inhibit the blah protein or bind to the blah receptor.

Most of the expense and difficulty getting most drugs approved isn't in showing some efficicacy against **some** endpoint but showing that the drug isn't too harmful and is net beneficial (not phrased this way but that's essentially what's behind debates about using intermediate endpoints like cholesterol rather than reduction in heart attacks). There are plenty of surgeries that we've found out would fail those standards.

---

Ultimately, while I believe the FDA imposes far too high a barrier on approving new medications (just require it to what it claims to do at the rate and side effects claimed not that it improve on existing meds) I think it's justifed for medications but not surgery exactly because it is soo much harder to figure out what surgeries are worthwhile.

There are just too many variables and the initial attempts are often failures. Transplants were death sentences ... until they weren't. Drugs are a single item that can be evaluated in it's complete form before approval. Surgery would never develop vital new techniques if it had to pass some general test of side effects vs benefits to be approved because surgeons would never learn until approval and absent training the method would languish.

Luckily, you are correct that the risks with surgery are lower. People are much less likely to undergo surgery, particularly a novel one, unless they have no other option. They might decide to take thalidomide just because they feel a bit nauseous.

Drug development for fatal diseases works poorly with the FDA: https://jakeseliger.com/2024/01/29/the-dead-and-dying-at-the-gates-of-oncology-clinical-trials/